Early Nineteenth-Century Actor Prints and the Emergence of the Utagawa School

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Tokugawa government (bakufu) had abandoned most of the measures it had tried to implement during the so-called “Kansei Reforms” of 1787-1793. There was also a gradual easing up of sumptuary regulations and censorship. The ensuing decades saw the return of a thriving urban culture that included the kabuki theatres and licensed quarters, as well as an expanding market for books (almost always illustrated) and prints. These were the heady days of the Bunka (1804-1818) and Bunsei (1818-1830) eras, which in Japanese cultural history are often taken together as the golden age of Edo urban culture. Indeed, it was during these years that ukiyo-e became a truly popular art (Kobayashi 92).

The period also confirmed the cultural dominance of the shogun’s capital, Edo. While for most of the first two centuries of Tokugawa rule (1600-1867) the ancient capital of Kyoto and the neighboring commercial hub Osaka had been at the forefront of new cultural developments, in the nineteenth century it was clearly the metropolis of Edo that set the standards. In the case of woodblock prints, for example, while Osaka artists continued to focus on actor prints for a clientele of kabuki aficionados, Edo publishers and artists not only stepped up production but took on a host of new subjects and formats.

Although the Kansei Reforms are generally seen as a failure, among the policies was an emphasis on education, which contributed to the spread of literacy and an increase in the number of kashi hon-ya or lending libraries (Keene 409). The publishing industry responded to the growing demand for reading material with a wide variety of genres, including practical how-to books, works of religious or moral instruction, and popular fiction. Fiction in particular saw a proliferation of new genres and formats. There were the love stories (ninjōbon), like Tamenaga Shusui’s Shunshoku Umegoyomi (Colors of Spring: Plum Blossom, 1832-33), the longer, more serious narratives (yomihon), such as Kyokutei Bakin’s masterpiece Nansō Satomi Hakkenden (Biographies of Eight Dogs, 1814-1841), and the gōkan, a less high-brow variety of long-form fiction, the best example of which is Ryūtei Tanehiko’s Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji (False Murasaki and a Country Genji, 1829-1842), a parodic updating of the eleventh century classic Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji).

This was also a golden age of the kabuki theatre, which not only produced stage versions of many of the works of popular fiction, but could also rely on its own playwrights, such as Tsuruya Namboku III (1755-1829), who had major successes with plays such as Sakura-hime Azuma Bunshō (Lady Sakura: Documents from the East, 1817), and Tōkaidō Yostuya Kaidan (Ghost Story of Yotsuya, 1825), a spin-off of the perennial favorite, Kanadehon Chūshingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers).

Star actors of the time included Matsumoto Kōshirō V, Iwai Hanshirō V, and Ichikawa Danjūrō VII, who in 1832 retook his previous name (Ebizō) so that his son could succeed to the title of Danjūrō VIII. Danjūrō VII’s relinquishment of the prestigious name in no way meant his retirement from the kabuki world, however. It was while acting for the second time as Ebizō that he began creating the canon known as the “Eighteen Kabuki Favorites” (Kabuki Jūhachiban), which includes the popular plays Sukeroku and Shibaraku, as well as Kanjinchō, a kabuki version of the Noh play Ataka, first staged in 1840.

The explosion of book publishing and the brilliance of the theatre were a boon to print designers. Many of the ukiyo-e artists of the period began as book illustrators. When they moved on to single-sheet prints, they were usually involved in the production of actor prints (yakusha-e), at least until the success of Hokusai and Hiroshige in the 1830s and 1840s made the landscape (fūkeiga) another popular genre. In the process, the bijinga, which had dominated ukiyo-e for most of the previous century, lost much of its currency.

At the forefront of this new era of the actor print was Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825). Tokyokuni was himself the student of Utagawa Tohoharu, who is recognized as the founder of the Utagawa school. It was Tokyokuni’s success as the preeminent designer of yakusha-e, however, and that of his students, who include Kuniyasu, Kunisada, and Kuniyoshi, that solidified the reputation of the Utagawa school and led to its members dominating the field of ukiyo-e for the rest of the century.

Kunisada (1786-1865), who eventually took the title of Toyokuni III, was arguably the most popular and certainly the most prolific of print designers during the nineteenth-century. Like his master, he specialized in actor prints, though he also produced bijinga, “samurai pictures” (musha-e), and even landscapes. He also worked on a number of collaborative series with artists such as Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige I and Hiroshige II. Kunisada’s students include Sadafusa, Sadahide, Kunisada II, and Kunichika.

Kuniyoshi and his students represent another line in the evolution of the Utagawa school. Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), like Kunisada, studied under the Tokyokuni I. He was thus well-schooled in turning out actor prints in the Utagawa style. He is best known, however, for his prints of historical and legendary heroes. Eventually he developed a style of his own, which was continued and in some cases further developed by his students, who include Yoshitoshi, Yoshitora, Yoshiiku, Yoshikazu, and Yoshimori.

The title of the Osaka print to the left, Isse Ichidai, indicates that this was a retirement or career finale performance. Ichikawa Ebijūrō I (1777-1827) acted under that name 1815-1827; Utaemon III (1778-1838) used his acting name 1791-1835. Since Ebijūrō I died in 1827, if this was his final performance with Utaemon, it would have occurred no later than that year. The British Museum dates this print to 1825. This is probably based on records of the play’s performance. According to the online data base Nihon Engeki Kōgyō Nenpyō, the play Hikosan Gongen Chigai no Sukedachi was performed at the Kado-za in Osaka in the third month of 1825.

References:

Keene, Donald. World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-modern Era, 1600-1867. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1976.

Kobayashi Tadashi. Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Trans. Mark A Harbison. Tōkyō, New York, London: Kodansha International, 1982.

Kunisada/Toyokuni III (1786 - 1864) 国貞(三代豊国)

The actors Seki Sanjūrō II, Iwai Tojaku I (Hanshirō V), and Nakmura Shikan II in the play Modori Kago Iro ni Aikata 『戻籠色相肩』1833

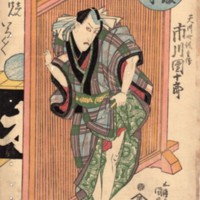

Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825)

The actors Matsumoto Kōshirō V as Fukushimaya Seibei and Iwai Hanshirō V as Geiko Kashiku in the play Kore ga katami Kōraiyajima (1808)

Utagawa Kunisada/Toyokuni III (1786-1865)

Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as Amakawaya Gihei in act ten of the play Chūshingura. 1827

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII in the role of Inue Shinbei in the play Hakkenden Uwasa no Takadono. 1836

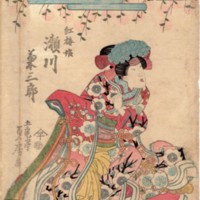

Utagawa Sadafusa (active 1825-1850)

The actor Segawa Kikusaburō in the role of Kōbai-hime. Circa 1830